CMU Has Reached 100 Years of Providing an Opportunity for a Better Life

The creation of Grand Junction Junior College in 1925 marked both the end and the beginning of two distinct eras, one without higher education and the other which has been marked by 100 years of excellence and innovation at what became Colorado Mesa University.

The push for higher education on the Western Slope began in the 1880s when communities jockeyed for advantage at the state legislature. The emphasis at that time was on securing a “normal school,” — the name for a school providing teacher training. Grand Junction was barely on the map, having been founded in 1882 and sat the first round out while Gunnison vied against Greeley to land the institution.

The State Normal School ended up being established in Greeley in 1889 and it would not be the only time political forces favoring Colorado’s Eastern Plains and Front Range would win out over the Western Slope.

According to CMU archivist Amber D’Ambrosio, co-author of A Century of the Maverick Spirit, a comprehensive, illustrated history of CMU’s first 100 years, it wasn’t until 1896 that the The Grand Junction Daily Sentinel touted Grand Junction as “the ideal location for a normal school.” While Grand Junction was not successful — the honor went to Gunnison — the idea of local higher education had been planted and would flourish over the next two decades.

Richard E. Tope arrived in the Grand Valley in 1918 to become the public school superintendent. An educator and historian, Tope immediately became a champion for local higher education, joining forces with the Chamber of Commerce, the Rotary Club, the Lions Club and the newspaper.

At about this same time, a new idea was taking hold across the United States: the idea of a junior college, a two-year institution which would prepare students to complete their baccalaureate degrees at larger universities. In 1920, University of Colorado (CU) President George Norlin proposed creating the state’s first junior college in Grand Junction. The community was thrilled. Not only was this a way for Grand Junction to provide higher education for local students, but it would position the community and the new college as innovators, even Mavericks.

As with anything involving politics, the process of actually establishing Grand Junction Junior College was convoluted and controversial. In 1921, a bill to create a junior college tied to the University of Colorado failed. In 1925, another attempt was made, this time suggesting the creation of an extension service junior college in Grand Junction. Championed by State Senator Ollie Bannister and Representative C.J. McCormick, the bill faced opposition from neighboring communities and counties also vying for higher education in their areas and from lawmakers on the Eastern Slope hoping to keep higher education funding closer to home and away from a faction within state government aligned with the Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

In the 1920s, politics, not only in Colorado but across the United States, were dominated by the Ku Klux Klan. In Colorado, the KKK held sway in the state house, but not the state senate. Governor Clarence Morley was also aligned with the Klan.

According to The Grand Junction Daily Sentinel reports from the era, the KKK faction opposed a junior college in Grand Junction, although as D’Ambrosio shared, “It’s really hard to know exactly what was going on and how much of it was the KKK and how much of it was other factors, just because there’s never been enough money to go around in the state of Colorado, particularly for higher education.”

In the end, Bannister, McCormick and community leaders persuaded Governor Morley to support the legislation and on April 20, 1925 — the last day of the legislative session — Grand Junction Junior College was established. But there was one significant wrinkle. Grand Junction had legal authority to create a junior college, but it would have to do so without significant state funding. Only $2,500 was appropriated and it was earmarked for the improvement of the college’s future site.

Without state support, the nascent junior college turned to the community that had wanted local higher education for so long.

With only months to prepare, the community, led by Tope, rallied.

Not wanting to wait for future state appropriations, the newly appointed trustees, Tope, C.E. Cherrington and D.B. Wright worked to find makeshift classroom space in existing public buildings. For a permanent site, they chose the old Lowell School at Fifth and Rood to house the new college. Built in 1884, it was derelict, abandoned by the school district in favor of the new Lowell School which was nearing completion.

Classrooms would need teachers and Tope took charge, releasing four high school teachers to teach part-time at the junior college. They received full pay from the school district. This move was especially consequential, as these first faculty members were not only skilled but also dedicated. One of them, Mary Rait, would become one of the first, if not the first, female college vice presidents in Colorado, retiring from Mesa College in 1960.

Until a local mill levy was passed in 1937, funding remained precarious, but Grand Junction’s goal to bring local higher education to the community since 1896 would keep the fire alive. A rallying community and local service clubs made mighty efforts to keep the college’s doors open and help retire its debt. Such support

allowed Grand Junction citizens to realize their dream of housing a place where their children could further their education close to home and boost the economic future of western Colorado.

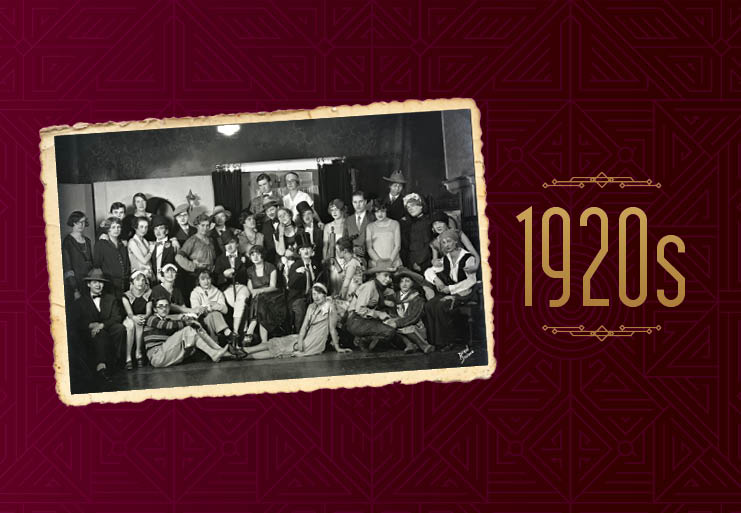

In the fall of 1925, Grand Junction Junior College opened its doors to 39 students, with two additional students enrolling for the spring semester. Since its inception, CMU has continued to grow, witnessing bursts of exponential growth throughout the years. And while CMU students have come from across the state, the nation and the world, the university remains committed to providing all levels of higher education in a remote and largely rural setting. It’s an incredible success story, much of which can be traced back to a small community with a big dream.

In his 1957 history of Grand Junction, Richard E. Tope recalled the community’s frustration with the lack of higher education in western Colorado.

“Mesa College we now have,” he wrote. “It is supported by the whole people and the service it renders meets the fondest dreams of the unyielding and resolute ideas of those pioneers who knew no such word as fail.”

68 years later, in 2025, CMU President Emeritus Tim Foster also credited the Grand Junction community for much of what CMU has become.

“We are about students, we are about this community,” he explained. “For 100 years, CMU has fought for every inch we gain, and everybody joins together. This is the sort of unifying mission this community understands.”